Paving the Path of Least Resistance

Design systems can sometimes feel like a shackle on the product development process. Where they are rigid, as is often required of design systems in order for them to succeed, they may slow down product teams when their coverage doesn’t extend to the requirements of the task at hand. When the system is too loose or ambiguous, it does a poor job of guiding the process in a way that prevents redundant or inconsistent work.

There are models of working with design systems—and the teams that maintain them—that can help subside the slowing of progress they sometimes impose, and instead create a virtuous cycle of feedback that helps the design system grow in a self-sufficient way.

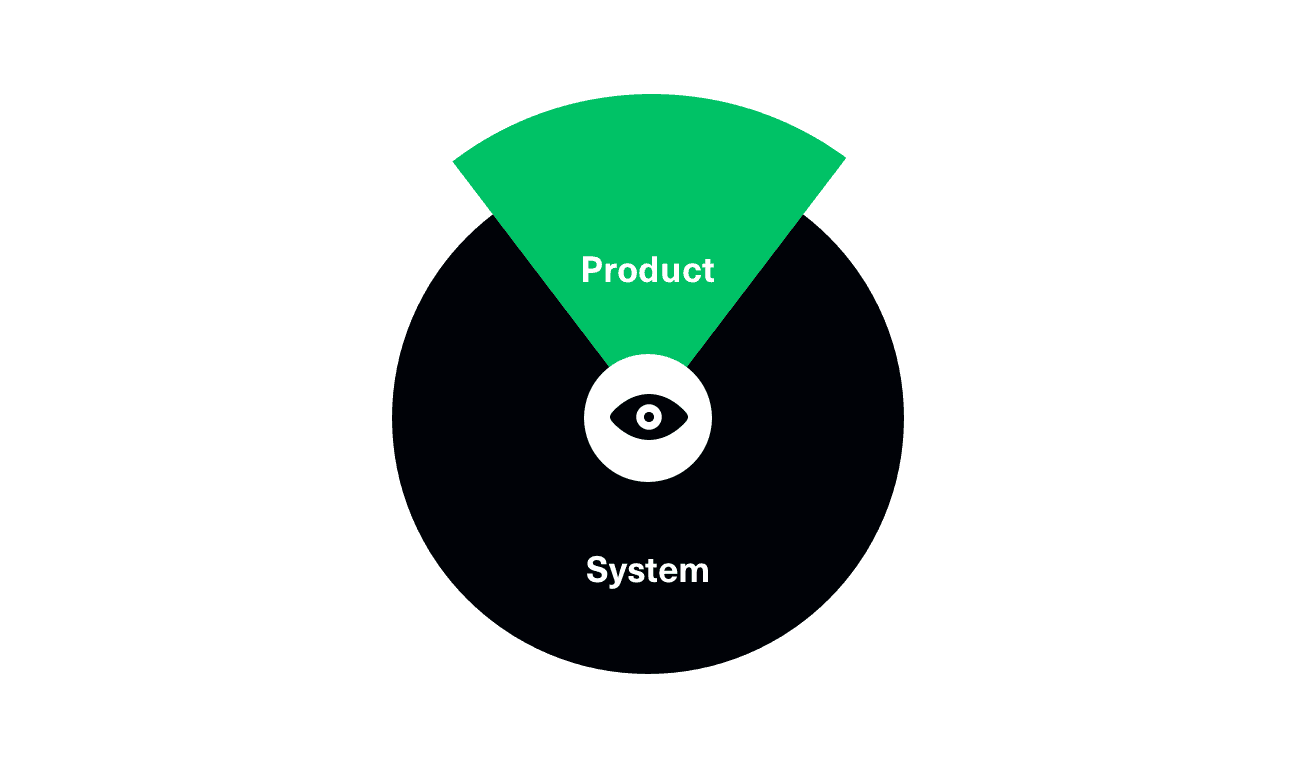

Rather than design systems acting as a guideline or a police-like force, the teams working on product development should allow its constituents—experts at their jobs—to do their best work, unhindered by the limits of the system. The job of the design systems team becomes largely an observational role; we observe the limits of the system, detect the abstracts of the problem the product team is trying to solve, and apply those abstracts to a solution that can be generalized to broader uses.

More concretely, product teams have a narrow yet extremely deep understanding of a particular problem set. They may, for instance, stretch a particular component in a system so thin that they need to build their own set of extensions to the component. Rather than preventing this kind of apparent misuse of the system, the design systems team should encourage it, since it reveals blind spots that are easy to miss when developing a general solution. They take what they can from the extensions and hacks necessary for that specific product team, and generalize them for use amongst other teams and in chorus with other components.

The resulting system should embody a well-defined set of broad rules; patterns that solve 80–90% of the problems faced by product development teams, that serve to prevent needless cycles of thought and work, and ensure greater consistency. The remaining 10–20% not well-covered by the system is where the product team exercises their expertise and imbues the product with a uniqueness that is expressive, but well within the expected style of the system.

When teams maintaining design systems are working closely with product teams in an embedded and observational way, this kind of output is inevitable. As I think more about the dynamic between design systems teams and product teams, it becomes apparent that systems rely on the product teams just as heavily, if not more, than vice versa. Without product teams to poke and prod at the system, stretch it, and break it, design systems would be built in a vacuum and their creators would be left with undeserved pride.

You can think of design systems much like paving roads. The busiest roads with the most commonly-trafficked routes are deservedly well-maintained, but they aren’t the only roads available. No matter the destination, it is the duty of those responsible for paving those roads to enable the travelers to arrive with haste and safety. It is a job that requires constant maintenance, and when done well, shouldn’t be noticed by its customers at all.

This post is one in a loosely-connected series of posts about design systems and the teams that maintain them. Other installments include a theoretical exploration of compositional design systems, and a collection of thoughts on how the relationship between designers and engineers should be approached.